Sorry for posting this late!

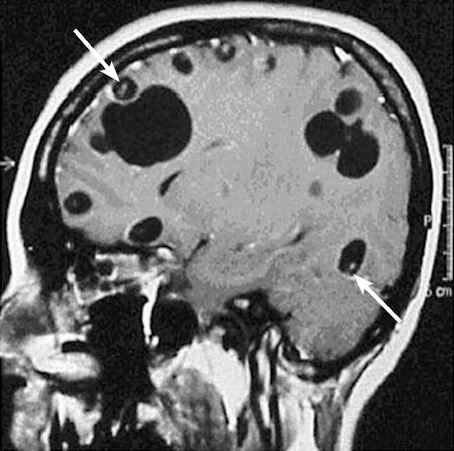

A 38yo M with history of asthma, but otherwise healthy, presents acute onset seizure as well as LLE, LUE weakness and paresthesia. He has never had seizures before prior to this. History revealed that patient was born in Honduras, and he grew up on a pig farm, and his brother actually had a history of Taeniasis. MRI revealed a cystic structure with a thin septae/soft tissue component within, consistent with neurocysticercosis!

Let’s talk about seizures for a little bit.

In developeED countries, the most common cause of epileptic seizure is often idiopathic.

In developING countries, the most common cause of epileptic seizure in both kids and adults, is neurocysticercosis (NCC).

Neurocysticercosis: When larvae form of the Taenia solium (aka the tapeworm) move to non-GI tissues and into CNS.

Presentation: Viable (asx, many years) -> degenerating (loses ability to evade immune system, localized inflammation) -> non-viable (calcified granulomas, can still cause szx)

- Intra-parenchymal

- Most common form of neurocysticercosis, > 60% of cases

- 3-5 years after infection but can occur > 30 years after initial exposure.

- Seizure = most common manifestation. Occur in setting of cysts degeneration or granulomas.

- Endemic areas: NCC is the most common cause of adult onset seizure

- Headaches, usually mild

- Rare complications: vision, focal neuro, meningitis, encephalitis (higher parasitic load)

- Most, however, are asx and diagnosed incidentally.

- Extra-parenchymal

- When NCC occurs in the spine, eyes, ventricles, subarachnoid space. More commonly in adults.

- Can cause increased ICH, hydrocephalous

- Sub-arachnoid form is most severe, esp in the basilar cisterns. 5% of cases.

- Spinal: 1% of cases, can cause localized/dermatomal pain.

- Ocular: 1-3% of cases, impaired vision, eye pain, diplopia, chlorioretinitis, retinal detachment.

- Extra Neural

- Most common: muscles, subcutaneous

- Cardiac has been described…

Diagnosis

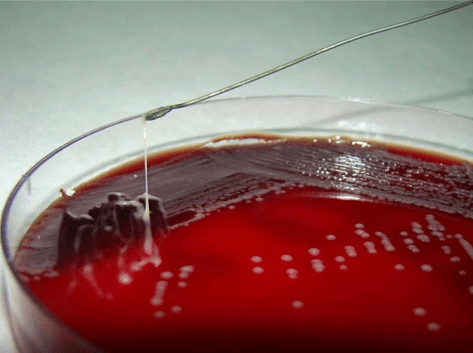

- Stool O&P can help

- Eosinophilia is uncommon

- Imaging: Clinical history, endemic history, enhancing cystic lesion on MRI is very likely.

- CT: Useful for IDing calcifications, parenchymal cysticerci, and eye involvement

- MRI: Useful for small lesions, degenerative changes, edema, and visualizing scolices within calcified lesion

(Mahale et al. Extraparenchymal (Racemose) Neurocysticercosis and Its Multitude Manifestations: A Comprehensive Review. J Clin Neurol. 2015 Jul;11(3):203-211)

- Serology: Should be performed for confirmation Enzyme Linked Immunoelectrotransfer Blot Ab is highly sensitive and specific, but takes time and availability is limited.

Management

- Latest IDSA Recommendation in 2018

- Calcified lesions: symptomatic management only with anti-epileptics

- Enhancing lesions

- Patients who acquired NCC in a non-endemic area should have their household members screened.

- Screen for latent TB, strongyloides infection given possibility of prolonged steroid use

- Fundoscopic exam is recommended for all patients with NCC

- Prior to anti-parasitic therapy, all patients should be treated with corticosteroids prior to initiation.

- Anti-epileptics should be used in all patients with seizures.

- Albendazole + praziquantel is better than monotherapy with albendazole if greater than 2 lesions. 1-2 lesions, monotherapy with albendazole should suffice.

- Intraventricular neurocysticercosis

- Minimally invasive surgical removal prior to antiparasitic therapy to minimize inflammatory response.

- Subarachnoid neurocysticercosis in the basilar cisterns or Sylvian fissures

- Prolong course of anti-parasitic until radiologic resolution, can last more than a year.

- Corticosteroids recommended while on treatment but methotrexate can be considered a steroid-sparing agent in patients requiring prolonged anti-inflammatory.

- Surgery case by case

- Spinal neurocysticercosis

- Combination surgery and anti-parasitics, start steroids first with evidence of spinal cord dysfunction and prior to antiparasitics

- Ocular:

- Surgery preferred over medical management.

Source: NEJM, Grepmed

Source: NEJM, Grepmed