A 41 (below 45 is young in my book) man with infrequent medical care, but otherwise no medical history other than obesity, presenting with acute onset chest pressure when he was showering. He initially tried to walk it off, but the pressure became sharp, and it started to radiate from the anterior chest to his shoulder blades. At the same time, he started feeling short of breath, dizzy, and diaphoretic. CTA revealed a Stanford Type B aortic dissection extending all the way to the R renal artery!

Chest pain: This is a topic we deal with almost every single day. In general, I like to classify chest pain in two categories:

Can’t Miss!

- ACS & associated complications

- Pulmonary emboli

- Pneumothorax

- Aortic dissection

- Tamponade

- Esophageal rupture

Everything Else!

- Infection (abscess, pneumonia, etc), arguably also belongs in the Can’t Miss category

- Peri/myocarditis

- Pleuritis

- Mass

- Effusion

- MSK

- Trauma

- etc

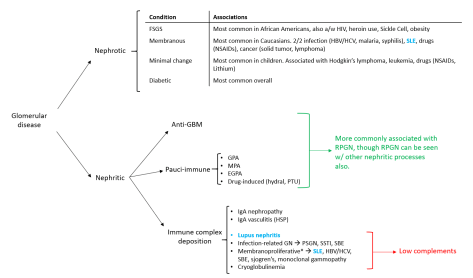

When it comes to dissection, there are two classification systems that describes the nature of the dissection (source: Grepmed). The Stanford classification is used more commonly.

Epidemiology

- Men > women

- Age 60-80 most common, mean age 63, 65% men

- Younger < 40: 34% with HTN, 8.5% with h/o Marfan

Other Risk Factors

- Trauma

- Hypertension (most important predisposing factor of acute aortic dissection, up to 72% of pts will have underlying HTN. HTN is more common in those with type B vs type A.

- Pheochromocytoma (very rare, case reports, thanks Alexa for pointing this out!)

- Connective tissue disorders

- Turner Syndrome

- Vasculitis

- Pregnancy

- Crack cocaine, meth

- Biscuspid aortic valve (9% of pts under age 40 have biscuspid AV)\

- Pre-existing aortic aneurysm

- Heavy lifting

- Cardiac cath

Pathophysiology:

- In a nut shell, due to a tear in the aortic intima, blood flow creates a false lumen separating the intima and the media. The higher the blood pressure, the higher the size of the false lumen due to shear force.

- 50-65% originate in the ascending aorta, while 20-30% originate near the left subclavian artery and extend distally.

Presentation

- Typical Triad

- Acute chest or abdominal pain, can be sharp, tearing, or ripping

- Pulse/pressure deficit between extremities

- Mediastinal/aortic widening on CXR

- Ascending aortic dissections are 2x as common as descending, 30% involves aortic arch

- Acute onset chest pain that radiates to the back is the typical illness script. Pain can be the classic tearing or sharp.

- Type A: more likely to experience anterior chest pain

- Type B: more likely to experience back pain or abd pain > anterior chest pain

- Propagation leads to acute AR, tamponade, stroke, shock, can propagate proximal or distally

Physical Exam Highlights

- You might have heard of a term called pulse/pressure deficit when it comes to aortic dissections. In a nut shell, if there is a difference in SBP of greater > 20mmHg between right and left, then there is a deficit. This deficit is only found in 30% of cases of its presence can be very useful. High specific but poor sensitivity.

-

Findings Sensitivity Specificity LR if Present LR if Absent Pulse Deficit 12-49% 82-99% 4.2 0.8 - Presence of an aortic regurg murmur has a LR of 1.5

- The presence of 3 findings increase likelihood of a Type A dissection:

- SBP < 100

- AR

- Pulse deficit

- Presence of mediastinal or aortic widening on CXR increases probability of dissection somewhat, with LR 2.0

Diagnosis

- CTA is fastest and easiest to get, 90+ % sensitivity and specificity

- Can also do MRA or echo (TEE preferred) but might get longer to arrange in our hospital

- EKG won’t have any specific signs but it can help you rule out other things.

Management/Prognosis

- Stanford Type A

- Surgical emergency, CT Surgery should be consulted ASAP.

- High mortality, 2% per hour if left untreated.

- Surgical mortality: up to 30%

- Typically open repair, role of endovascular repair is not well studied.

- Stanford Type B

- Uncomplicated:

- Medical management, goal is to reduce BP < 120/80 and HR < 60

- Medical management:

- Beta blocker: Esmolol or labetalol or propranolol, first line

- Vasodilator: Nicardipine or nitroprusside, can cause reflexive tachycardia, hence do NOT use alone and only add if BP remains elevated with beta blocker

- Nitroprusside over time can lead to cyanide toxicity

- CCB: Non-DHP i.e. verapamil or diltiazem if there is a contraindication to beta blockers

- Complicated:

- If impending aortic rupture, end organ damage, continuing pain and hypertension despite medical therapy, false lumen extension, or large area of involvement, Type B is now considered complicated.

- Endovascular intervention with Vascular Surgery is recommended (INSTEAD-XL study)

- Uncomplicated:

- Long term management

- Identify associated genetics factors

- HR, HTN control

- Serial imaging: 3, 6, and 12 months after event, and then annually after initial episode