Thanks to Joe for presenting the case of an elderly man with no known medical history who presented with acute AMS, found to have L facial swelling and crepitus, eventually diagnosed with necrotizing Ludwig’s angina!

Clinical Pearls

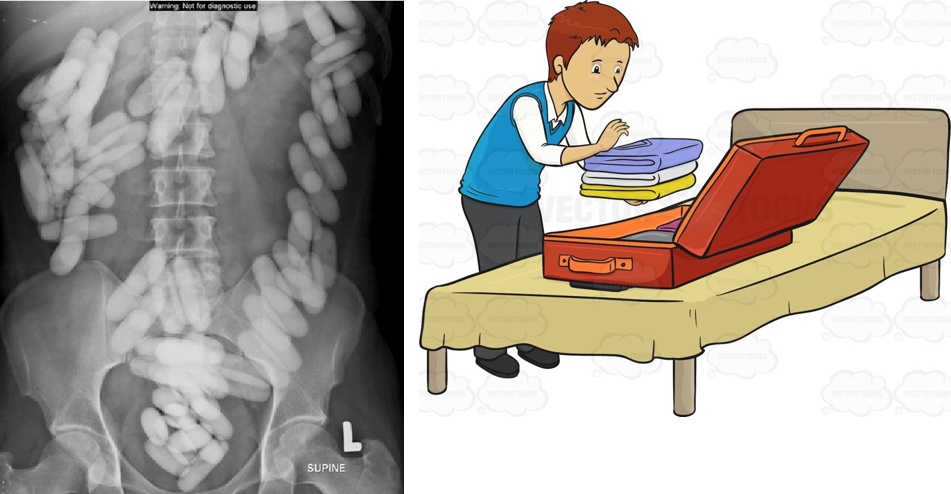

- Necrotizing fasciitis (NF) is a surgical diagnosis and involves infection of muscle and subcutaneous fat.

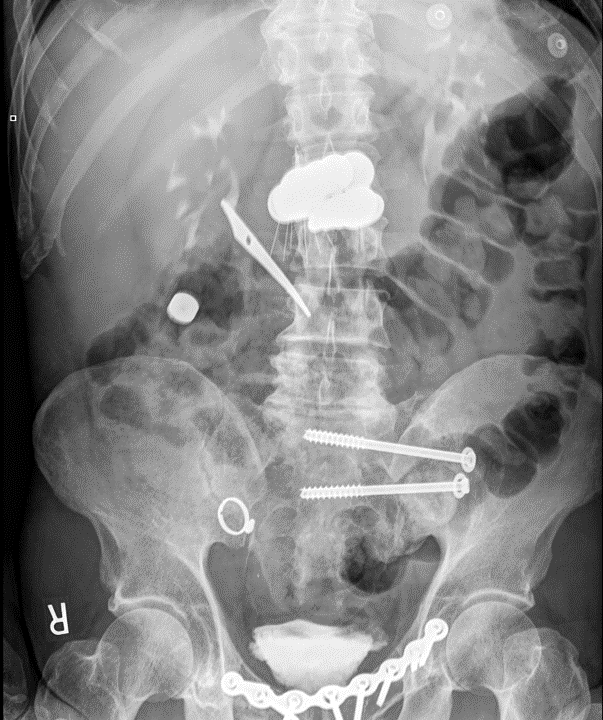

- CT is a useful tool to help with diagnosis and in one case series had a 100% sensitivity and >80% specificity for diagnosing NF.

- LRINEC or Laboratory Risk Indicator for NF is a lab-based risk assessment tool to help risk stratify patients with possible NF. It has a sensitivity of 80% and specificity of 67%. It should NOT supplant your clinical judgement.

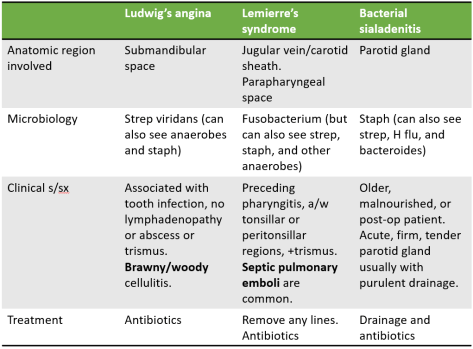

- Ludwig’s angina refers to any infection of the submandibular space (not just NF). Normally the treatment for Ludwig’s angina is antibiotics. In the case of NF, urgent surgical debridement is necessary. In spite of antibiotics and debridement, head and neck necrotizing infections are associated with a high mortality rate (~40%).

- In patients with Ludwig’s angina, always involve anesthesia AND ENT to help secure airway. Oral intubation is associated with higher rates of laryngospasm in these patients so oftentimes nasal intubation is preferred.

Deep neck infections:

Necrotizing fasciitis

- Background

- Infection of deep tissues, specifically muscle fascia and subcutaneous fat.

- Two main types

- Type 1: polymicrobial

- More common in elderly and those with significant comorbidities including diabetes, immunocompromised states, PVD, etc.

- Blood cultures are positive in ~20% of patients.

- Type 2: monomicrobial (usually GAS but can be other beta-hemolytic strep and MRSA)

- Can be seen in any age group and without any underlying disease.

- Type 1: polymicrobial

- Clinical manifestations

- Remember that you do not need to have a penetrating injury for NF. Oftentimes, blunt trauma is the preceding history and overlying tissue does not show any signs of infection, leading to the “pain out of proportion to exam” finding.

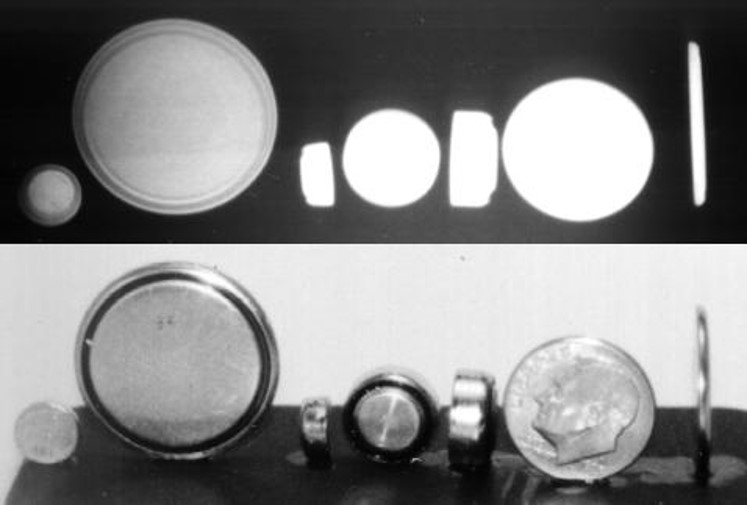

- Systemic signs of toxicity (including hypotension and shock), rapid progression, crepitus.

- LRINEC or the Laboratory Risk Indicator for NF is a lab-based risk assessment tool to help risk stratify patients with possible NF.

- It has a sensitivity of 80% and specificity of 67%. It should NOT supplant your clinical judgement.

- CT scan is highly sensitive (100% in one case series of 67 patients) and specific for differentiating NF from celllulitis.

- Ultimately, NF is a surgical diagnosis so consult surgery early if you are concerned about the diagnosis and before waiting for imaging in an unstable patient!

- Treatment

- Early surgical intervention and debridement

- Empiric antibiotics

- Beta lactam/beta lactamase inhibitor or carbapenem PLUS

- vancomycin or other similar drug for MRSA coverage PLUS

- clindamycin

- Eagle effect: at high bacterial loads, there is reduced efficacy of beta-lactam antibiotics for strep pyogenes infections due to reduced exposure of penicillin binding protein on the bacteria. Clindamycin works better in these situations and does not rely on the penicillin binding protein site.

- Toxin neutralization: clindamycin has the ability to suppress synthesis of bacterial toxins that cause systemic symptoms in patients with NF.

- Other therapies such as hyperbaric oxygen and IVIG have not shown reliable evidence of benefit in studies and are not currently recommended by the IDSA.

- Prognosis

- Mortality is high even with appropriate treatment (up to 45%).

References:

Refer to this amazing review by NEJM for more info on NF.